Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide, and while many are familiar with traditional risk factors like high LDL cholesterol, high blood pressure, and diabetes, there’s a lesser-known but significant player in cardiovascular risk: Lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a). This unique lipoprotein has emerged as an independent risk factor for heart disease, yet remains underrecognized in routine clinical care. In this post, we’ll explore Lp(a)’s discovery, structure, pathophysiology, associated risks, and treatment options.

The Discovery and History of Lipoprotein(a)

Lipoprotein(a) was discovered in 1963 by Norwegian geneticist Kåre Berg[7]. In his groundbreaking work, Berg was actually searching for new genetic serum blood types when he immunized rabbits with isolated β-lipoproteins from a single individual who, by chance, had elevated Lp(a)[2]. This serendipitous event led to the generation of immune antisera that reacted positively in about one-third of healthy humans. Berg named this previously unknown factor “Lp(a)” and demonstrated its heritability through family studies[2][6].

The significance of Berg’s discovery cannot be overstated. As noted in historical accounts: “If he did not have the good fortune that the donor of the β-lipoproteins also had sufficiently elevated Lp(a) to generate an immune response to apo(a), the immunization experiments would have simply generated rabbit antibodies to human LDL-apoB, and the discovery of Lp(a) would likely have occurred much later”[2].

By 1974, Berg had already linked the presence of Lp(a) to coronary heart disease, though confirmation required improvements in measurement assays[6]. The human gene encoding apolipoprotein(a) was successfully cloned in 1987, providing crucial insights into its structure and relationship to plasminogen[6][7].

Understanding Lp(a) Structure and Biochemistry

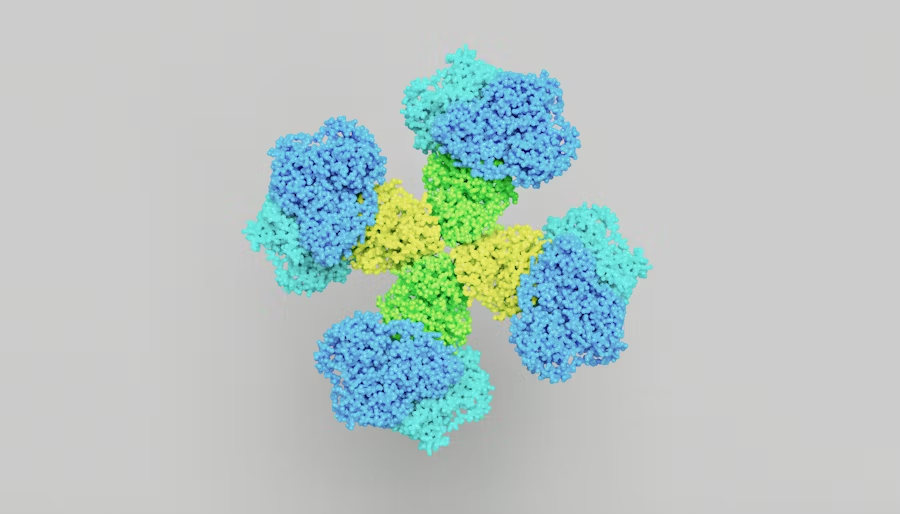

Lipoprotein(a) has a complex structure that contributes to its unique pathophysiological effects. At its core, Lp(a) resembles LDL cholesterol but with critical differences:

- Lp(a) contains an apolipoprotein B-100 (apoB-100) particle, similar to LDL[10]

- What makes Lp(a) unique is the addition of apolipoprotein(a) [apo(a)], which is covalently bound to the apoB-100 particle[1][10]

- Lp(a) also contains oxidized phospholipids (OxPL), which contribute to its inflammatory properties[10]

The apo(a) component of Lp(a) evolved through duplication of the plasminogen gene but lacks sequences encoding plasminogen kringles I to III. Instead, it encodes 10 kringle IV subtypes followed by one plasminogen kringle V-like domain and an inactive protease region[6]. This structural similarity to plasminogen, a protein involved in blood clot dissolution, helps explain some of Lp(a)’s thrombotic properties.

Pathophysiology: How Lp(a) Causes Cardiovascular Damage

Lipoprotein(a) contributes to cardiovascular disease through multiple mechanisms:

Atherosclerosis Promotion

Lp(a) can accumulate in arterial walls, forming plaques similar to LDL cholesterol[1]. These plaques can block blood flow to vital organs such as the heart, brain, kidneys, and lungs, leading to conditions like heart attacks, strokes, and other cardiovascular diseases[1].

Prothrombotic Effects

Due to its structural similarity to plasminogen, Lp(a) can interfere with normal clot dissolution, promoting thrombosis. This increases the risk of acute cardiovascular events like heart attacks and strokes[6].

Inflammation

Lp(a) contains oxidized phospholipids that promote inflammation in the arterial wall, accelerating atherosclerosis[10][6]. This inflammatory component distinguishes Lp(a) from regular LDL cholesterol and contributes to its pathogenicity.

Aortic Valve Stenosis

Beyond atherosclerotic disease, Lp(a) has been strongly linked to calcific aortic valve stenosis, a progressive narrowing of the aortic valve that can lead to heart failure[5][8].

Genetic Determinants of Lp(a) Levels

One of the most important aspects of Lp(a) is its strong genetic determination. Approximately 70% to over 90% of the variation in Lp(a) levels between individuals is genetically determined[6]. This makes Lp(a) predominantly a monogenic cardiovascular risk determinant, unlike many other risk factors that are influenced by multiple genes and environmental factors[6].

The LPA gene, which encodes apolipoprotein(a), is the primary determinant of Lp(a) levels. Variations in this gene, particularly in the number of kringle IV type 2 repeats, significantly influence Lp(a) concentration in the blood[6].

Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Elevated Lp(a)

High Lp(a) levels are associated with an increased risk of various cardiovascular conditions:

Coronary Heart Disease

Elevated Lp(a) levels of 50 mg/dL (125 nmols/L) or higher significantly increase the risk of heart attacks[1][8]. This risk is independent of other traditional risk factors, including LDL cholesterol.

Stroke

Lp(a) has been consistently linked to increased stroke risk, particularly ischemic stroke[8].

Aortic Valve Stenosis

High Lp(a) is a causal risk factor for calcific aortic valve stenosis, a condition that can lead to heart failure if untreated[5][8].

Peripheral Arterial Disease

While the evidence is less conclusive than for coronary disease, elevated Lp(a) has also been associated with peripheral arterial disease[8].

Risk Amplification with LDL Cholesterol

Importantly, the cardiovascular risk associated with high Lp(a) is amplified when LDL cholesterol is also elevated. In the Framingham Heart Study, individuals with both high Lp(a) (≥100 nmol/L) and high LDL-C (≥135 mg/dL) had the highest absolute risk of cardiovascular events, reaching 22.6% over 15 years[3]. Even in individuals with only moderate elevations of LDL-C (135-159 mg/dL), the presence of high Lp(a) identified individuals at high risk, equivalent to those with LDL-C ≥160 mg/dL[3].

Who Should Be Tested for Lp(a)?

Given the genetic determination of Lp(a) levels, testing is particularly important for:

- Individuals with a family history of premature cardiovascular disease

- Patients with cardiovascular disease despite well-controlled traditional risk factors

- Those with familial hypercholesterolemia

- Patients with calcific aortic valve disease

- Individuals with intermediate cardiovascular risk where additional risk stratification would influence treatment decisions

It’s important to note that Lp(a) testing should be considered regardless of coronary calcium score results. While coronary calcium scoring provides valuable information about existing atherosclerotic burden, it doesn’t capture the thrombotic and inflammatory risks associated with elevated Lp(a). Therefore, a normal calcium score does not exclude the risk conferred by high Lp(a) levels.

Current Treatment Approaches for Elevated Lp(a)

Managing elevated Lp(a) presents unique challenges because, unlike LDL cholesterol, Lp(a) levels are minimally affected by lifestyle modifications. Current treatment approaches include:

Aggressive Management of Other Risk Factors

Since elevated Lp(a) amplifies the risk associated with other cardiovascular risk factors, aggressive management of LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking is essential[5].

Statins

While statins effectively lower LDL cholesterol, they may actually increase Lp(a) levels by 8% to 24%[4]. However, the clinical implications of this increase remain unclear, and the overall cardiovascular benefit of statins likely outweighs any potential harm from modest Lp(a) elevation.

Niacin

Niacin can reduce Lp(a) levels by 20% to 30%, but clinical trials have failed to demonstrate significant cardiovascular benefit with niacin therapy[4].

Lipoprotein Apheresis

For patients with very high Lp(a) levels and progressive cardiovascular disease despite optimal medical therapy, lipoprotein apheresis is an option. This procedure, similar to dialysis, can reduce Lp(a) levels by approximately 60-70%[4][9]. In a retrospective cohort study, lipoprotein apheresis resulted in a 64% and 63% mean reduction in LDL-C and Lp(a), respectively, and a 94% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events[4].

Emerging Therapies for Lp(a) Reduction

The development of targeted Lp(a)-lowering therapies has generated significant excitement in the cardiovascular community:

Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs)

ASOs are 16- to 20-nucleic acid-long DNA fragments that are complementary to LPA mRNA. They enter hepatocytes where ribonuclease H1 cleaves the ASO-mRNA complex, resulting in decreased LPA mRNA and consequently decreased Lp(a) production[4].

Pelacarsen (also known as AKCEA-APO(a)-LRx or TQJ230) is a second-generation ASO currently being tested in a phase 3 clinical trial called Lp(a)HORIZON. In phase 1/2a trials, pelacarsen reduced Lp(a) by 26.2% to 85.3% at 30 days in single-dose groups, and by 66% to 92% in multidose groups[4][9].

Small-Interfering RNA (siRNA) Therapies

Similar to ASOs, siRNA therapies target LPA mRNA expression. Through N-acetylgalactosamine conjugation (gal-NAC), these therapies achieve more efficient hepatic uptake, promising increased tolerability and decreased complications[9].

PCSK9 Inhibitors

While not specifically designed to lower Lp(a), PCSK9 inhibitors have been shown to reduce Lp(a) levels by approximately 20-30%, though the mechanism and clinical significance of this reduction remain unclear[5].

The Importance of Family History in Lp(a) Assessment

Given the strong genetic determination of Lp(a) levels, family history plays a crucial role in risk assessment. Individuals with a family history of premature cardiovascular disease should be considered for Lp(a) testing, even in the absence of traditional risk factors.

The presence of elevated Lp(a) in a family member should prompt cascade screening of relatives, similar to the approach used for familial hypercholesterolemia. This strategy can identify individuals at high risk before clinical manifestations of cardiovascular disease occur, allowing for early intervention and prevention.

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

The clinical management of elevated Lp(a) is evolving rapidly as our understanding of its pathophysiology improves and new therapies emerge. Several key points warrant emphasis:

- Lp(a) measurement should be considered once in everyone’s lifetime to identify those at increased genetic risk for cardiovascular disease[5].

- For individuals with elevated Lp(a), aggressive management of other modifiable risk factors is essential, with particular attention to LDL cholesterol levels.

- The validation of the “Lp(a) hypothesis” – that lowering Lp(a) levels will lead to clinical benefit – is currently being tested in three major clinical outcome trials[2].

- Standardization and harmonization of Lp(a) assays remain challenges that need to be addressed to improve risk assessment and treatment decisions[6].

Conclusion

Lipoprotein(a) represents an important, genetically determined risk factor for cardiovascular disease that has been underrecognized in clinical practice. As we enter an era of precision medicine, understanding and addressing Lp(a)-associated risk will become increasingly important for comprehensive cardiovascular risk management.

The development of targeted Lp(a)-lowering therapies offers hope for reducing the residual cardiovascular risk that persists despite optimal management of traditional risk factors. While we await the results of ongoing clinical trials, clinicians should consider Lp(a) testing in appropriate patients and implement aggressive risk factor modification in those with elevated levels.

By integrating Lp(a) assessment into cardiovascular risk evaluation, particularly in the context of family history, we can improve risk stratification and potentially prevent cardiovascular events in high-risk individuals. The future of Lp(a) management looks promising, with the potential to further reduce the global burden of cardiovascular disease.

Sources

[1] Lipoprotein (a) Meaning and How Does it Impact My Heart Health? https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/cholesterol/genetic-conditions/lipoprotein-a-risks

[2] Lipoprotein(a) in the Year 2024: A Look Back and a Look Ahead https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.319483

[3] Risks of Incident Cardiovascular Disease Associated With … https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.119.014711

[4] Clinical Trial Design for Lipoprotein(a)-Lowering Therapies https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.02.033

[5] Lipoprotein(a): Emerging insights and therapeutics – PMC https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11033089/

[6] Lipoprotein(a): A Genetically Determined, Causal, and Prevalent … https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/ATV.0000000000000147

[7] Lipoprotein(a) – Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lipoprotein(a)

[8] Lipoprotein(a) as a Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Diseases https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10531345/

[9] Specialty Corner: Lipoprotein (a) Medications Under Development https://www.lipid.org/lipid-spin/spring-2022/specialty-corner-lipoprotein-medications-under-development

[10] What is Lipoprotein(a)? – Family Heart Foundation https://familyheart.org/what-is-lpa

[11] Lipoprotein(a): What it is, test results, and what they mean https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/lipoprotein-a-what-it-is-test-results-and-what-they-mean